Under a grey morning sky, engineers cluster around a tablet as strong winds tear their voices apart. On the screen, a red marker inches forward across a digital map of the ocean floor. Far beneath the waves, a robotic drill slowly cuts into ancient rock, marking the first metres of what could become the longest underwater rail tunnel ever built. There are no ceremonies or speeches, only the steady hum of generators and the shared understanding that a historic engineering project has quietly begun. The plan is a deep-sea train line linking continents that have until now only been connected by planes or undersea cables, redefining how distance and geography are experienced.

For years, the idea of a high-speed rail tunnel running beneath an ocean sounded like science fiction. Engineers treated it as a theoretical exercise, something that was technically possible but too risky and complex to attempt. That perception has now shifted. Construction preparations are underway, contracts have been signed, and survey vessels are actively mapping the seabed. Custom-built tunnel-boring machines designed to operate under extreme pressure are being assembled at coastal facilities, reflecting an ambition that goes far beyond conventional rail projects. The objective is a continuous rail corridor that allows passengers and freight to travel beneath the sea instead of relying on long-haul flights.

The transition from concept to reality did not come through a single political announcement but through years of data collection and technological progress. Extensive seabed mapping revealed stable rock formations where instability was once assumed. Advances in pressure-resistant tunnel linings, artificial intelligence-assisted drilling, and real-time seismic monitoring gradually reduced uncertainty. What was once dismissed as too dangerous became difficult but achievable, changing attitudes among engineers, regulators, and investors.

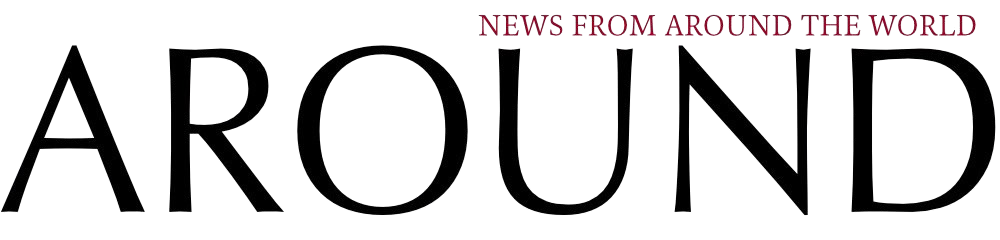

Building a train line under the ocean begins on land, at carefully selected portal sites where massive access shafts are drilled deep underground. From there, tunnel-boring machines move through solid bedrock beneath the seabed, avoiding softer sediments above. Each metre of tunnel is reinforced with steel-fibre concrete segments fitted together with extreme precision. Progress is slow and deliberate, measured in metres per day, with every stage monitored by sensors tracking pressure, temperature, and structural movement. Logistics are complex, requiring every component to be planned months in advance, as there is no margin for error far offshore and hundreds of metres below the sea floor.

Emergency planning is a critical part of the project. Engineers prepare for scenarios such as power failures, flooding, or equipment becoming stuck deep beneath the ocean. Redundant systems, pressurised refuges, independent oxygen supplies, and clearly defined escape protocols are built into the design. This focus on preparation and risk management is essential to making such an ambitious project viable in one of the planet’s most hostile environments.

If completed, an underwater rail tunnel could significantly change how people think about travel and global connectivity. Journeys that currently require long flights could be completed by train, reducing reliance on aviation and offering a lower-emission alternative powered by renewable energy. Cities on different continents could begin to feel more closely connected, influencing where businesses operate, how supply chains are designed, and how institutions collaborate across borders. The idea of crossing an ocean could shift from an exceptional event to a routine part of daily life.

There are also broader social and environmental implications. As concerns about climate change grow, rail travel is increasingly seen as a more sustainable option compared to flying. An underwater rail link offers a way to reduce aviation emissions without sacrificing mobility, appealing particularly to younger generations who prioritize environmental responsibility. While costs and accessibility remain challenges, the project represents a long-term investment in cleaner, more resilient infrastructure.

Behind the scenes, the human element of the project is just as important as the technology. Work proceeds in carefully managed shifts, with every section of tunnel documented and inspected. Some teams are experimenting with controlled-pressure living and rest areas to reduce health risks for workers operating in extreme conditions. Project leaders emphasize the importance of transparent communication with coastal communities, explaining potential impacts and addressing concerns directly rather than relying on technical jargon.

This underwater rail tunnel challenges the traditional idea of the ocean as a barrier. Instead, it reframes the sea as a corridor, a space through which people and goods can move quietly beneath the surface. While the project will not solve global political or economic inequalities, it has the potential to reshape perceptions of distance and connection. In the future, traveling between continents by train could feel as ordinary as commuting within a city, marking a profound shift in how humanity navigates the planet.